A Verywell report: these foods are the biggest culprits of foodborne illness

Fact checked by Nick Blackmer

COVID-19 interventions from masking to increased hand washing meant fewer cases of flu, RSV, and even foodborne illness outbreaks during the pandemic.

But since many pandemic safety protocols have fallen by the wayside, foodborne germs have been making a comeback since 2022.

Infections caused by bacteria like E. coli, Salmonella, and Listeria are back to pre-pandemic levels, according to a report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).1

There are also increasing cases of infection from Vibrio, a “flesh-eating” bacteria found in raw seafood; Yersinia, a bacteria in undercooked pork; and Cyclospora, a parasite often linked to imported produce.

The CDC report is based on data from only 10 states, but it’s representative of national trends.

As we tried to understand which foods are the biggest culprits behind illness, we dove into CDC’s National Outbreak Reporting System (NORS), which was launched in 2009 to integrate data collected through the Waterborne Disease and Outbreak Surveillance System and the Foodborne Disease Outbreak Surveillance System. Much of the data is incomplete and disorganized, which highlights the challenges in tackling food safety systemically.

Contamination along the food supply chain—from poultry slaughter to agricultural water—is responsible for many recent foodborne outbreaks. As a consumer, you can try to protect yourself by learning about foods that are prone to infectious bacteria and ways to prepare food safely.

Which Foods Cause the Most Foodborne Illness Outbreaks?

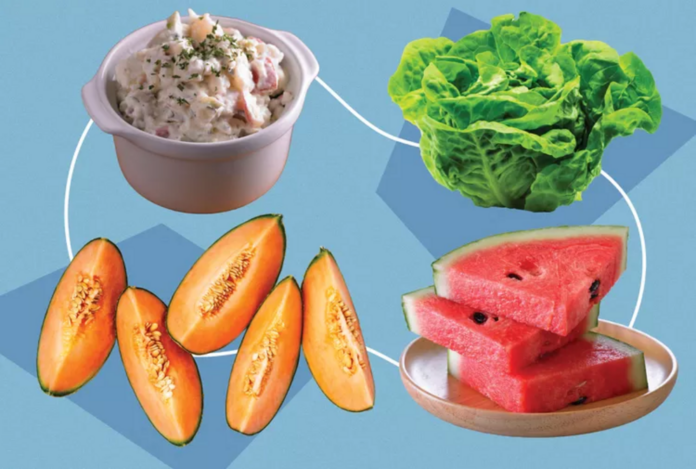

According to data from CDC, one summer dish is particularly prone to foodborne bacteria: potato salad. People often blame mayonnaise in the salad as the culprit because it contains eggs, but that’s a myth.2

“It’s not the mayonnaise. Mayonnaise is actually a little bit acidic and a little bit protective,” said Jennifer Quinlan, PhD, a professor of nutrition sciences specializing in food safety at Drexel University.

Ingredients in a salad are usually handled directly through chopping or tossing, which is a major way of transmitting foodborne bacteria.

While potato salad has caused over 5,000 illnesses in the last two decades, it’s not the germiest dish. Chicken—whether it’s grilled, baked, chilled, or barbecued—is the single food item that commits the most offense to the stomach. At least 5% of the total foodborne illness cases recorded to date are related to chicken.2

Chicken is a major source of Salmonella, a bacteria that can cause a gastrointestinal infection with symptoms like diarrhea, fever, and abdominal cramps. The CDC estimated that one in every 25 packages of chicken at the grocery store is contaminated with Salmonella.3

Campylobacter, a germ that’s often linked to raw or undercooked chicken, is a leading cause of bacterial diarrheal disease and food poisoning. But most of these cases are preventable with proper food handling and hand washing.4

What Are the Most Common Foodborne Bacteria?

Salmonella and norovirus are the two most common sources of foodborne illnesses in the United States. Over 43% of cases are attributed to some type of norovirus, while almost a quarter is caused by Salmonella, according to CDC data.

Norovirus

Salads made up a large number of the foods that carried norovirus, a fecal-oral virus that can be transmitted by dirty hands. For salads that contain lettuce, the vegetable could have been contaminated with norovirus during harvest, Quinlan explained.

“If salads aren’t washed appropriately or if they’re handled by a sick food handler they can become transmitters for norovirus,” she said. “This risk can be exacerbated by fields often being difficult places to maintain great sanitary conditions.”

Salmonella

As opposed to norovirus, Salmonella risks are concentrated around meats, specifically poultry, pork, and eggs. Salmonella is almost impossible to eradicate from the chicken supply completely—once a bird is infected, it’s very difficult to remove the bacteria from it, Quinlan said.

Both the chicken meat and the egg yoke can contain Salmonella. “The latest data shows that Salmonella might be present in about one in 20,000 eggs,” Quinlan added.

E. Coli

Much like Salmonella in chickens, Escherichia coli (E. coli) is another bacteria that’s hard to remove from cows.

This is why ground beef is by far the most common food associated with shiga toxin-producing E. coli, which is responsible for many foodborne outbreaks.

E. coli is also present in many wild animals that live near fields where other foods are being grown, Quinlan said. Vegetables like lettuce and spinach are grown in the soil, which can be exposed to animal feces or water contamination.

Listeria

Another familiar foodborne bacteria, Listeria, is less common than Salmonella and E. coli. But it sticks out in the CDC data because of its severity. Illnesses from Listeria had a hospitalization and death rate over four times higher than the next highest source, shiga toxin-producing E. coli infections.

Listeria is such a dangerous bacteria in large part due to its unique hardiness—it’s the only pathogen that can grow at refrigerated temperatures, according to Quinlan. This means once a food has been infected, even storing it at sub-40 degrees Fahrenheit will not eliminate the risk of transferral.

Some of the most typical foods that carry Listeria are melons because they’re grown in the ground. Listeria can also spread between infected foods through utensils, so a knife that’s used to cut multiple melons can easily transmit the bacteria. One of the most deadly foodborne outbreaks in the U.S. was a Listeria outbreak in 2011 traced back to cantaloupe in Colorado that killed 33 people.

4 Simple Food Safety Measures

There are four steps you can take to lower the risk of getting sick from or transmitting foodborne illnesses: Clean, separate, cook, and chill.5

Cleaning includes washing hands with soap and water for at least 20 seconds before, during, and after preparing food or eating. You should also rinse fruits and vegetables under running water before preparing or consuming them.

To keep your kitchen and dishware clean, wash utensils, dishes, cutting boards, and exposed countertops with hot soapy water after use.

However, cleaning does not include washing raw meats like poultry, fish, or beef. Although some people tend to wash store-bought chicken before cooking, Quinlan said this practice is not just ineffective, but actually increases the risk of foodborne illness.

Washing ingredients like raw chicken will not remove most common bacteria like Salmonella, but rather allow the bacteria to travel to other foods or surfaces in the kitchen through aerosolization, she explained.

What About Dining Out?

About 64% of all illnesses in foodborne illness outbreaks were attributed to either some type of restaurant, caterer, or banquet facility, according to CDC data.2 Although it’s much harder to control for food safety factors in these settings, you can pay attention to an establishment’s food safety rating and any obvious food safety hazards, like unsanitary bathroom areas or foods that are left out for too long at room temperature.

The best practice is to separate raw and cooked foods when preparing them, so you can cut the risk of cross-contamination. This is especially prevalent when handling raw meat, poultry, seafood, and eggs. Preparing these types of foods on separate cutting boards and storing the raw foods in separate sealed containers can further diminish the chances of cross-contamination of foodborne illness.

Whole cuts of beef, veal, lamb, pork, and fish should be cooked to a minimum of 145°F, while ground meats like beef and pork to 160°F. Poultry, leftovers, and casseroles should be cooked or heated to 165°F. You can use a meat thermometer to ensure you’re cooking to the correct temperature.

You might prefer runny eggs, but eggs are the safest when cooked thoroughly, Quinlan said.

If you have leftovers, they should be refrigerated at a minimum below 40°F or frozen at 0°F or below. Bacteria can germinate rapidly at temperatures above 40°F so perishable food should be stored within two hours of preparation.

Malfunctioning or broken refrigerators could also lead to foodborne illness infections, Quinlan said. You can use either a built-in or additional thermometer inside your fridge to make sure it’s working properly.

If you’re generally a healthy person, getting infected with a foodborne illness might mean several days of diarrhea and an upset stomach. But for young children, older adults, and those who have a weakened immune system, they’re at acute risk for developing some of the most severe symptoms that often result in hospitalization or death.

While there are a variety of illnesses you can contract from many different types of food, the methods to keep yourself safe stay the same: Clean carefully, separate completely, cook thoroughly, and chill immediately.

Methodology

Foodborne illness data is only for outbreaks reported to the CDC’s National Outbreak Reporting System (NORS). NORS data available for foodborne illnesses is only from 1998 to 2021 at the time of writing.

Illnesses, hospitalizations, and deaths with multiple foods and/or etiology were attributed in full to each food or etiology. Many general food ingredients with numerous variations, like “baked chicken,” “barbecue chicken,” “grilled chicken,” etc. were treated separately in data visualizations. Outbreaks with “unknown,” “multiple,” or missing foods listed as well as “other” or missing etiologies were excluded. Foods and etiologies with fewer than 384 illnesses were less than the minimum sample size and excluded.

For the rest of this article please go to source link below.

For full references please use source link below.