First-ever amber discovered in Antarctica shows rainforest existed near South Pole

Imagine a time machine that could whisk you back to the age of the dinosaurs. Suddenly, you find yourself in a dense, swampy forest, with insects buzzing between flowers, ferns, and conifers.

Believe it or not, you’re standing in West Antarctica.

Scientists in Germany and the UK have now discovered amber there for the first time – the fossilized ‘blood’ of ancient coniferous trees that once grew on Earth’s southernmost continent between 83 and 92 million years ago.

Along with fossils of roots, pollen, and spores, the amber provides some of the best evidence yet that a mid-Cretaceous, swampy rainforest existed near the South Pole, and that this prehistoric environment was “dominated by conifers“, similar to forests in New Zealand and Patagonia today.

The unearthing of amber in Antarctica pulls back the continent’s current icy exterior to reveal an ancient habitat once warm and wet enough to host resin-producing trees. In the mid-Cretaceous, those trees would have had to survive through months of total darkness over winter.

But survive, they clearly did. Even if they had to go dormant for long chunks of time.

Before this discovery, scientists had only found Cretaceous amber deposits as far south as the Otway Basin in Australia and the Tupuangi Formation in New Zealand.

“It was very exciting to realize that, at some point in their history, all seven continents had climatic conditions allowing resin-producing trees to survive,” says marine geologist Johann Klages from the Alfred Wegener Institute in Germany.

“Our goal now is to learn more about the forest ecosystem – if it burned down, if we can find traces of life included in the amber. This discovery allows a journey to the past in yet another more direct way.”

Scientists have unearthed fossilized wood and leaves in Antarctica since the early 19th century, but many of these discoveries date back hundreds of millions of years to when the southern supercontinent Gondwana existed. As Antarctica drifted away from Australia and South America toward the South Pole, it’s not entirely clear what happened to its forests.

In 2017, researchers drilled into the seafloor near West Antarctica and pulled up exceptionally well-preserved evidence of these long-lost habitats.

After several years of analysis, Klages and a team of researchers announced in 2020 that they had found a web of fossilized roots that dated back to the mid-Cretaceous. Under the microscope, they also identified evidence of pollen and spores.

That same drilling has now offered up concrete proof that resin-producing trees once existed in Antarctica.

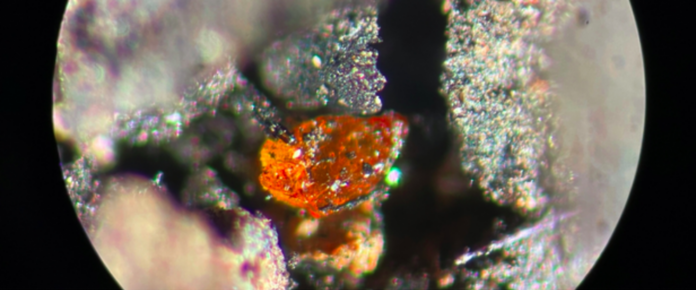

In a 3-meter (10-foot) long layer of mudstone, Klagen and a new team have described several tiny slices of translucent amber, just 0.5 to 1.0 millimeters in size. Each hosts a variation of yellow to orange colors with typical scalloped fractures on the surface.

This is a sign of resin flow, which occurs when sap leaks out of a tree to seal the bark against injuries from fires or insects.

The Cretaceous was one of the warmest periods in Earth’s history, and volcanic deposits found on Antarctica and nearby islands show evidence of frequent forest fires during this time.

The amber was probably preserved and fossilized because high water levels quickly covered the tree resin, protecting it from ultraviolet radiation and oxidation.

It even looks like the amber contains some tiny bits of tree bark, but further analysis is needed to confirm that.

Piece by miniscule piece, scientists are gradually putting together a picture of what Antarctica’s forests once used to look like and how they functioned 90 million years ago.

The study was published in Antarctic Research.