Chopped-up human bones in Guatemalan cave came from Maya sacrificial murders

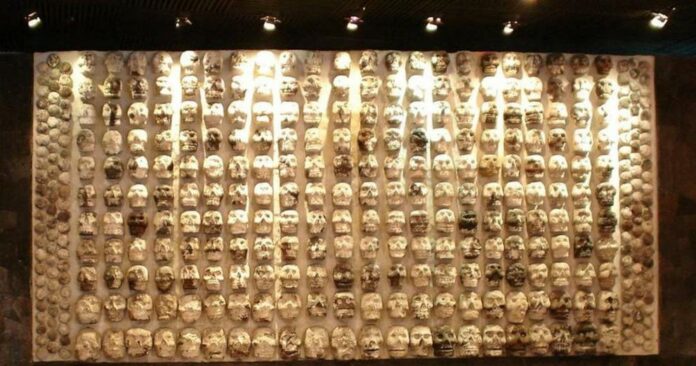

Top image: Display of wooden rack filled with skulls, used by Mesoamerican societies (including the Maya) to display the heads of sacrificial victims, at the Templo Mayor Museum in Mexico City.

Beneath the ancient Maya city of Dos Pilas in northern Guatemala, archaeologists recently made a grim discovery that reveals the lengths the Maya would go to in order to curry the favor of the gods at harvest time. Deep within a flooded cave known (appropriately enough) as Cueva de Sangre, or “the Cave of Blood,” the archaeologists uncovered hundreds of fragmented human bones, many of which bore unmistakable marks of violent attacks (many were literally chopped into pieces). The nature of the remains clearly suggested that ritual sacrifices of human beings had occurred, which apparently took place nearly 2,000 years ago.

The Cave of Blood is part of a network of subterranean chambers located beneath Dos Pilas, and was first mapped in the early 1990s. Dated to between 400 BC and 250 AD, the caves were used by the Maya during times of prosperity, and it seems that Cueva de Sangre was reserved for sacrificial rites tied to seasonal change and agricultural activities.

Bioarchaeologist Michele Bleuze of California State University, Los Angeles, who has been studying the chopped-up bones found in Guatemala, noted a curious fact about the remains that have been discovered so far.

“The emerging pattern that we’re seeing is that there are body parts and not bodies,” she told Live Science. “In Maya ritual, body parts are just as valuable as the whole body.

Violent Rituals to Appease Bloodthirsty Gods

This fragmentation, researchers believe, is central to understanding the purpose of the cave. Bones were found lying openly on the surface of the cave floor, not buried as in traditional funerary contexts. The presence of red ocher, a pigment used in many ancient rituals, and obsidian blades — a sharp volcanic glass favored in Maya ceremonies — supports the theory that Cueva de Sangre was not a tomb but a sacred site were blood sacrifices were frequently performed.

The physical condition of the bones provides the most indisputible evidence of ceremonial violence. Forensic anthropologist Ellen Fricano of Western University of Health Sciences examined the skeletal injuries and noted multiple instances of trauma inflicted around the time of death. These include sharp-force marks on a forehead fragment, likely made with a beveled blade, and a similar cut on a child’s hip bone. The choice and precision of tools suggest intentional dismemberment rather than random violence or battle wounds.

“There are a few lines of evidence that we used to determine that this was more likely a ritual site than not,” Fricano explained to Live Science.

Alongside the cuts and fractures, the spatial arrangement of the bones appears deliberate. In one chamber, four skull caps were discovered stacked neatly. This is a sign, the archaeologists say, that the remains were carefully handled and displayed as part of the rituals that were taking place.

The cave’s layout also provides important context. Accessible only by a narrow opening that leads to a low passage and then opens onto a pool of water, Cueva de Sangre would have been flooded for most of the year. The dry season — roughly between March and May — was likely the only time the site could be reached.

This timing may be key to understanding the purpose of the sacrifices. May 3 marks the Day of the Holy Cross, a ritual still observed by some modern Maya communities. The day occurs just before the annual rains begin and includes visits to caves to petition for rain and agricultural success.

The archaeologists responsible for the latest finds at Cueva de Sangre believe the sacrifices that took place there so long ago were tied to this ancient plea for seasonal renewal. Offering body parts or entire individuals could have been seen as a way to appease the Maya rain god, Chaac, to ensure he would be in a charitable mood over the coming months.

Intense Maya Spiritual Practices Revealed

Discoveries of human sacrifice-related artifacts or skeletal remains is not unusual at Maya archaeological sites. Nevertheless, the Cueva de Sangre findings provide an especially vivid and well-preserved demonstration of how sacrificial rituals were staged and carried out in the ancient Maya culture.

The distinction between burial and sacrificial space is paramount to understanding the Maya culture. While Maya burials were typically respectful, sacrifices were performative, meaning they were meant to provoke a specific response from one or more Maya deities. The exposed bones, signs of trauma, and ritual objects paint a haunting picture of a ceremony that was no doubt violent and shocking yet still designed to ensure a positive outcome for the Maya people as a whole.

Researchers emphasize that much work on the skeletal remains is yet do be done. Ancient DNA analysis and isotopic testing are underway to determine the origins, health, and relationships of those sacrificed.

“Right now, our focus is who are these people deposited here, because they’re treated completely differently than the majority of the population,” Bleuze said.

While the dismemberment of the corpses was violent and extreme, it was done in a context that was seen as sacred in ancient Maya society. The people must have been convinced that their prosperity was linked to these practices, otherwise they wouldn’t have continued to offer human sacrifices to their gods for so many centuries